Prepare for the Polemic.

Months ago, I stumbled across this article in Medical Decision Making called "The Fallacy of a Single Diagnosis" by Don Redelmeier and Eldar Shafir (hereafter R&S). In it they purport to show, using vignettes given to mostly lay people, that people have an intuition that there should be a single diagnosis, which, they claim, is wrong, and they attempt to substantiate this claim using a host of references. I make the following observations and counterclaims:

- R&S did indeed show that their respondents thought that having one virus, such as influenza (or EBV, or GAS pharyngitis), decreases the probability of having COVID simultaneously

- Their respondents are not wrong - having influenza does decrease the probability of a diagnosis of COVID

- R&S's own references show that their respondents were normative in judging a reduced probability of COVID if another respiratory pathogen was known to be present

Imagine that you're a 911 operator.

Operator: "911, what's your emergency?"

Caller: "My house is on fire and my car was stolen."

You would be incredulous. That is, unless there was one malefactor who has it in for the caller, set his house ablaze then stole his car for a getaway (a "unifying diagnosis" of the crime). Similarly, the simultaneous occurrence of two infections may be due to a single "malefactor", viz, a reservoir for disease containing more than one pathogen. This is well-known epidemiologically. Sex workers often have coinfections with multiple pathogens, such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, HIV. Alternatively we could look at their environment (poverty, squallor), or their behaviors (promiscuity) as common risk factors for multiple pathogens. R&S agree with us there as they state later.

But the fact of the matter is, my coauthor and I spent years taking care of COVID patients, most all who were tested with extensive respiratory viral panels, and while we did see co-infections, it was the exception rather than the rule. And our intuition from that experience was, if you test positive for influenza, you're not going to also test positive for COVID simultaneously, because statistically it's unlikely, common risk factors and reservoirs notwithstanding. So we find our intuitions at loggerheads with those of R&S. How ever will we resolve the dispute?

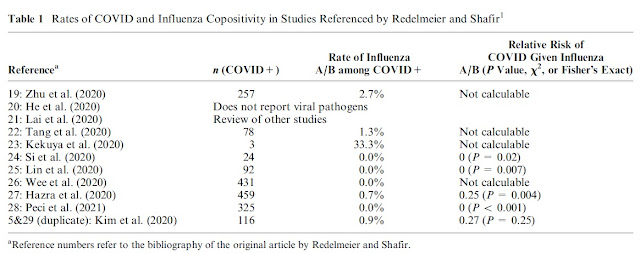

By looking at the data! And the very data they referenced and which we summarized in Table 1 of our letter shows that it is quite unlikely to test positive for COVID if you have influenza! (For the record, we did not test people for mono and strep throat during the pandemic - those strike a different population than the adults we cared for and their use in the vignettes by R&S is peculiar.) The data bear out experienced clinicians' intuitions, although the data were not complete and are subject to biases like publication bias. But what are we to conclude? That having influenza does not reduce the probability of COVID because R&S will it to be so?

In paragraph 3, R&S dredge up yet another study, purporting to show the rate of co-infections in COVID. It is not at all clear why, from among hundreds of epidemiological studies in COVID that they selected one describing 606 critically ill children admitted to an ICU in Brazil. Their study vignettes described adults. Be that as it may, R&S in their new Table 1 summarizing the study have transposed the conditional. We are now looking at the probability of another virus given COVID. Their vignettes asked about the probability of COVID given another virus. So I'm not sure how to make sense of this table. Furthermore, the the majority of "co-infections" in this study are rhinovirus and a virus I had not even heard of before: human bocavirus? (Looks like it's a commensal.) The clinical significance of both of these viruses, which accounted for 53% of viruses co-occurring with COVID in this study, is dubious at best. But that's beside the point: they have reversed the question to the probability of detecting another virus given COVID, and distracted us from some very obvious basic math:

To wit, of all the sick kids in this Brazilian pediatric ICU, only 24% had more than one virus! (And that's including clinically insignificant ones like rhinovirus - exclude those, and you're talking like 12% had more than one virus.) If you're a betting type and you know that and then I tell you, "Here's a kid in this ICU. He has X virus. Do you wanna bet he has just that virus, or bet that he has more than one virus? What's your bet?" Your bet is that he has just the single virus, which is just what our Table 1 for influenza showed and that's also just how R&S respondents answered the vignettes!

In paragraph 4, R&S state that our notion of what kind of data could really answer the "single diagnosis" question and inform the diagnostic process is an unreasonable proposition, and return to their own data, generated from majority layperson respondents.

In paragraph 5, they dismiss all of the relevant desiderata of an investigation of diagnostic thinking, and return to their approach that "emphasized the informal intuitions that underpin subjective COVID risk perceptions." Yet, from these "informal intuitions" bereft of the heft of formal decision making principles and grounding, they are willing to conclude that the notion of a "single diagnosis" is a fallacy? This is preposterous!

In paragraph 6, R&S miss the point that the presumption of a single diagnosis inheres in the Wells Score, the most widely used clinical decision aid. That's the only point, and it was missed. "Not because it is impossible that..." in our letter.

In paragraph 7, we are introduced to reductio ad absurdum, whereby we no longer make diagnoses in elderly men like Joe Biden, we just call it "old age". But, to be honest, I'm not sure I even completely understand the arguments of paragraphs 6&7.

In paragraph 8, in addition to an acknowledgement of some common ground between us, R&S betray yet again their haphazard approach to citation in their articles. Their last reference is the first one of the original "single diagnosis" article, one by Thorburn, 1918, called "The myth of Ockham's razor." They use this reference to support the statement "We believe, therefore, the conflicting debates around Occam’s razor have endured for centuries and will not end soon."

Have R&S read Thorburn's article? Thorburn does not dispute the principle of parsimony itself, rather, he acknowledges its validity:

"The unfortunate carelessness of Tennemann and Hamilton has engendered a very serious philosophic corruption. For, it has turned a sound rule of Methodology into a Metaphysical dogma."

Thorburn's entire article is not about the verity of Ockham's razor as a philosophical principle, but rather the glib and uncritical way attributions of the principle to the Franciscan Friar Sir William of Ockham have persisted and multiplied through the centuries. I wonder what Thorburn would have to say about the way his article is being cited a century after it was written.

A curious corrigendum was published about this article, in which now-reference 5 was not even published at the time the index article was published. Hmmm

ReplyDeletehttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10552328/

A year later, I continue to be astounded by how haphazard and sloppy this article is.

ReplyDeleteIn addition to our letter to the editor which was published, I submitted a private letter to the editor demonstrating that about half of the references in the original article were either irrelevant, misleading, or worked against the referenced statement. Some of them were self-citations. This was the impetus for the corrigendum, which, as noted above, now has a reference that was not extant at the time they published their article. They are now post hoc trying to cover their sloppiness. I find this all very shameful, and it reflects very poorly on the peer review process, which one might infer gives an easy pass to some researchers because of their status in the field. Which begs the question: is that status deserved?